Wavy Hair and Courtly Chaos: 5 Facts About Sandro Botticelli

He painted myth like it was gossip

Botticelli turned ancient mythology into Renaissance high drama — love triangles, kidnappings, flower explosions. If Florence had reality TV, he’d be the storyboard guy.

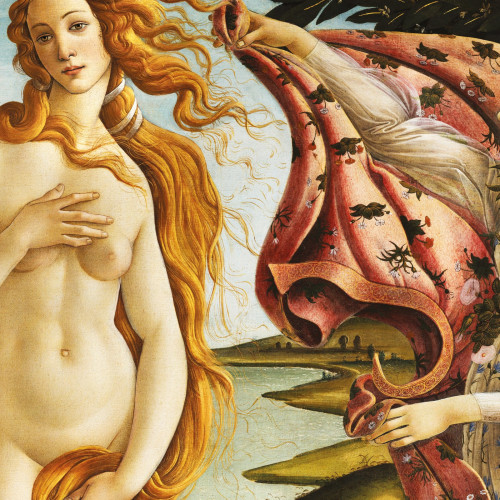

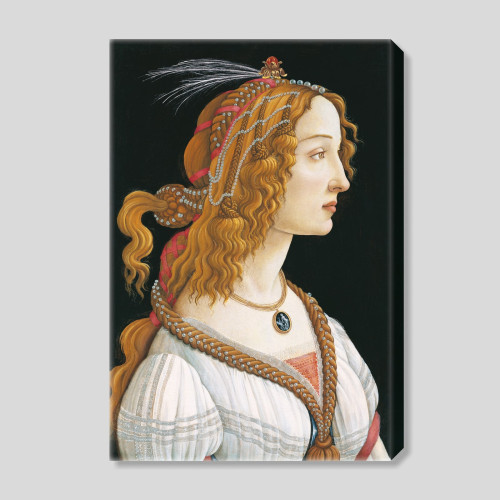

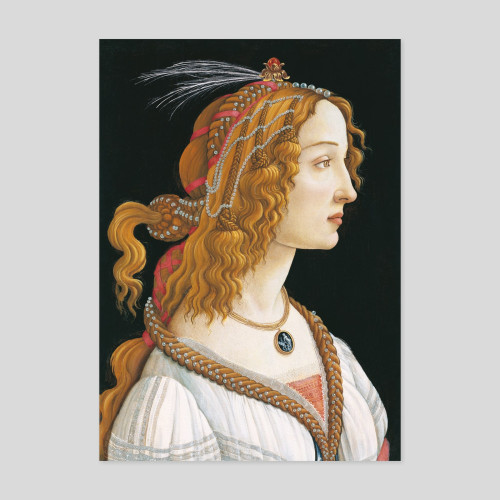

He had a thing for hair

No one painted golden waves quite like him. Every lock in his paintings looks like it was styled by a Florentine hair deity. Even the wind gods seem to have product in.

He probably never left Florence

While other artists traveled for fame or church gigs, Botticelli stayed loyal to his hometown. He painted gods, saints, and strange nymphs — all without needing to pack a suitcase.

Dante was his fan-fiction project

Later in life, he illustrated "The Divine Comedy" — as in, drew dozens of scenes from Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. Because what’s retirement without some infernal poetry?

He faded out, then came back strong

Botticelli’s fame dipped after his death — big time. But centuries later, art historians pulled him back into the spotlight. Now he's in museums, textbooks, and probably your tote bag.