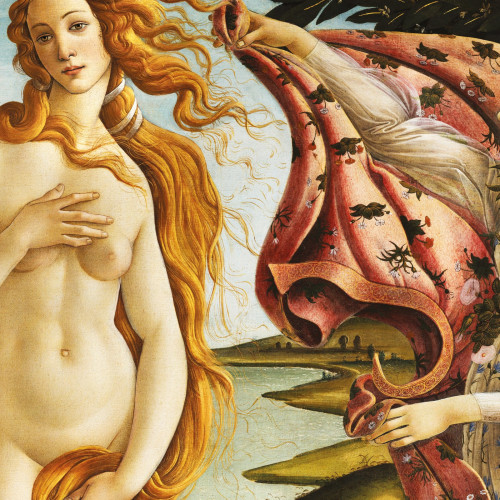

Seashell Arrivals and Windy Nudity: 5 Facts About Botticelli’s "The Birth of Venus"

Seashell taxi, myth edition

Venus doesn’t walk — she glides in on a scallop shell like it’s totally normal transportation. Poseidon didn’t sign off on this, but style takes precedence over seaworthiness in Renaissance myth logistics.

She might be freezing

She’s fresh out of the sea, completely unclothed, and the wind gods are going full blast. Someone bring this goddess a towel — or at least a cloak that isn’t made of roses.

That hair has a job to do

Venus’s hair is not just decorative — it’s strategically placed like the world’s oldest censorship blur. Renaissance modesty, courtesy of deluxe golden waves.

The wind gods ship her

On the left, Zephyrus and Aura blow her to shore like they’re launching a perfume commercial. Relationship goals? Maybe. Hazardous winds? Definitely.

No one is looking at the shell

It’s huge. It’s shimmering. It could feed a Florentine banquet. But everyone’s pretending it’s normal — because when a goddess arrives, you don’t question the seafood platter she rides in on.